The goal of the QEP is to enhance the ability of students to formulate relevant questions, critically evaluate discipline-specific literature whether health-related or academic/business-related, make better decisions, and improve outcomes.

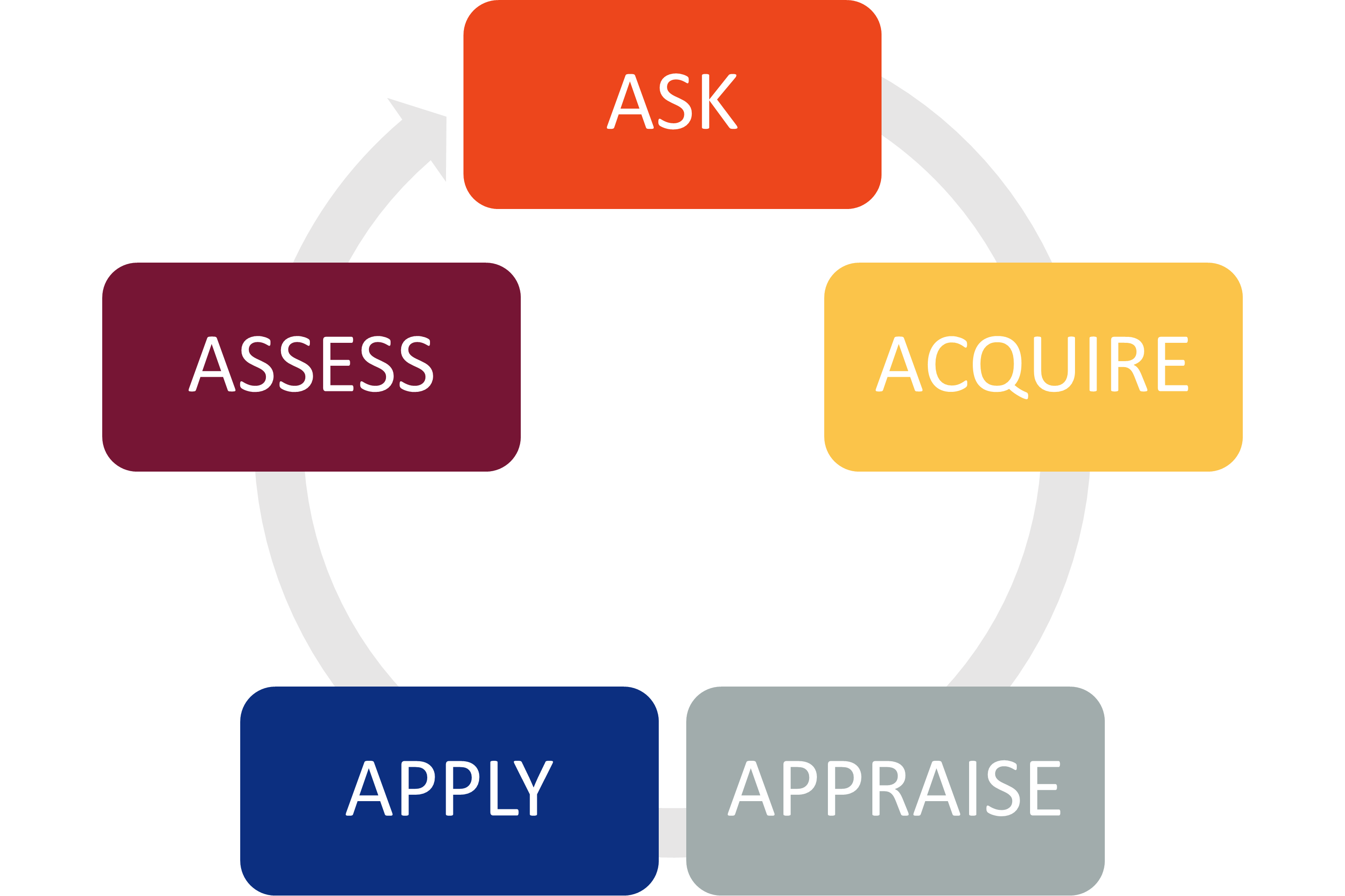

The 5 A Framework

Many of the degree programs at Parker University are healthcare or healthcare related. As a result, many of our faculty and students are familiar with Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) or similar construct which guides clinical decision-making. To frame our QEP Enhancing the Use of Evidence, we decided to use the 5 steps of evidence-based practice, also known as the 5 A’s. Using a familiar framework as a foundation for our plan builds on foundational knowledge and creates common language for implementation. The 5 A’s are: ask, acquire, appraise, apply, and assess. These 5 A’s promote a data-driven decision-making process by presenting five easy-to-follow steps.

- Ask: The first A is asking a question. This requires individuals to take the problem or task and turn it into a searchable question (Heneghan and Badenoch, 2006). The task could be a patient interaction, business plan, nutrition consultation, cybersecurity case study, or anything else related to students’ disciplines.

- Acquire: The second A is acquire - sometimes referred to as access. In the acquire stage, individuals find data, information, and evidence to answer the question they devised in the first step (Heneghan and Badenoch, 2006). This requires students to access information sources, such as journal databases, to obtain the data needed to answer their searchable question.

- Appraise: After asking a question and locating information, critical appraisal of those sources is necessary to understand the validity, impact, applicability, and potential biases within those sources (Heneghan and Badenoch, 2006). Appraising the sources requires critical thinking skills and encourages students to interrogate information for its value.

- Apply: The fourth A in the 5 A’s is apply, which involves applying the data to the original question or scenario while also considering the beliefs, values, content knowledge, motivations, and more that are present in the scenario (Heneghan and Badenoch, 2006). Information literacy and critical inquiry are especially important for teaching students to locate and apply evidence (Horntvedt et al., 2018). Students need to be aware of their own biases, as well as the stakeholders involved in the original problem – like clients, patients, or vendors.

- Assess: In the final stage of the 5 A’s, individuals must evaluate how the previous 4 A’s were utilized in the decision-making process and what changes to make for the next iteration of the process (Heneghan and Badenoch, 2006).

It is important to note, that while EBP is directly related to clinical scenarios and patient outcomes, it has applicability across disciplines who have similar concepts (e.g., market analysis steps, health promotion program planning, software development processes, etc.). For example, in a business setting, market analyses are used to drive planning. For History courses, searching for historical accounts or case studies may inform thematic analysis. These are just two of many ways in which our students can use data or research to address various scenarios. For those new to the concepts of EBP or data-driven decision-making, the 5 A’s serve as a protocol for obtaining and applying information to a scenario. This creates a common language for our QEP and drives the creation of assessment tools. While emerging from a healthcare context, this framework is applicable across academic programs and departments.